Thin Film Interference

oil slick photo by Cottonbro Studio on Pexels

oil slick photo by Cottonbro Studio on Pexels

bubble photo by Сергей Буланов on Pexels

bubble photo by Сергей Буланов on Pexels

The rainbow colors produced by a thin layer of oil or soap are produced by wave interference resulting from refraction yet again. Importantly there must be three layers for the light to interact with, and the middle one must be very thin. Common examples are a thin layer of oil on water, a coating on glass, and a soap bubble, where air is the first layer for all three (air is also the third layer in the soap bubble).

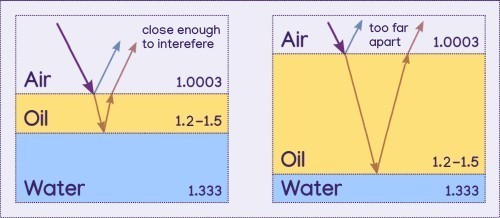

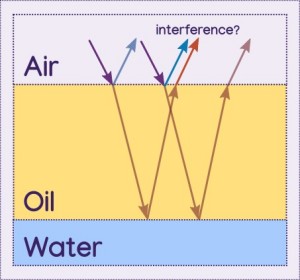

Light hits the second material where some of it will reflect, and some of it will pass through. The portion of light that enters the second material will then hit the third material which it will reflect off of. It exits the second material at the same angle that the first reflection made, but slightly further away, due to refraction and the distance it travelled within the second material. It is parallel to the initial reflection. Note that some light will also pass through the third material despite not being illustrated.

The wavelength of the wave and the distance the light travels through the second layer determines if the two parallel light paths' peaks and valleys will line up with one another or not. If they line up, the waves constructively interfere, meaning that color of light is amplified. If one wave's peaks overlap the other wave's valleys, they destructively interfere, cancelling each other out so that there is less light of that color.

The above diagram shows the parallel waves moving towards each other, which does not actually happen, it was just done to show how they overlap, since the thinness of the film means they will still be overlapping, rather than spread apart from one another.

Note on destructive interference

The parallel paths do not entirely cancel each other out unlike shown in the destructive interference animation. The intensity is lessened, but the refracted wave will have lost light when it hit the third layer, since some of the light would have traveled into it, rather than all of it reflecting. Since its intensity is less than the initial reflected wave, it cannot fully counteract.

Because each color of light has its own wavelength, this means that different thickness of a certain material will reinforce different colors of light, but not others. If the second layer is a uniform thickness, the color seen at an angle will just be one, instead of a rainbow assortment. A variation in colors occurs with a variation in thickness. Only a slight variation is needed though, since visible wavelengths are very tiny (400nm - 700nm).

Why thin?

For these paths to be close enough to interfere, the second material must be thin. If the material is too thick, the extra distance that the refracted light path takes within said material will take it too far away from the initial reflected light path, and they will not be close enough to interact.

But wait, couldn't the reflection of a light path interfere with the exit of another light path?

Keep in mind that wavelengths are very small, so the effects of interference are only noticeable when the second layer is very thin, just like how supernumerary rainbows are only noticeable when the raindrops are small. The further the distance the waves travel, the thinner and easier the distinct bands of color get washed out.

Determining Color from Thickness

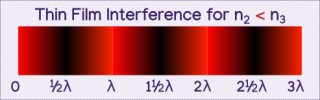

So how do we determine what thickness results in which color? We see a color if the distance traveled within the second layer is a multiple that wavelength, the interfering paths will line up peak to peak, valley to valley. (This is assuming the second layer's index of refraction is less than the third layers index of refraction, n2 < n3)

d = m*λ

Where d is the distance traveled in the second layer, λ is the wavelength, and m is a whole number (1,2,3...). You could separate the equation into: d1 = λ, d2 = 2λ, d3 = 3λ, etc.

This just means that as long as the distance traveled is a multiple of the wavelength, said wavelegth will constructively interfere! For example light at 400nm will show when the distance is 400nm, 800nm, 1200nm, etc.

You might be able to guess that exactly between these values, 400nm light will dissapear due to destructive interference: 600nm, 1000nm, 1400nm, etc.

d = m*λ + ½λ

We add half a wavelength because that is the distance between a peak and a valley, thus the offset needed to create destructive interference. Again we could separate the equation into parts: d1 = λ + ½λ, d2 = 2λ + ½λ, d3 = 3λ + ½λ, etc.

If we plug 400nm into d2 = 2λ + ½λ, we get d2 = 2*400 + ½*400 which is 800 + 200 = 1000

Note that the distance traveled can be shorter than a wavelength, meaning d0 = ½λ (d0 = 0*λ + ½λ) will also produce destructive interference. Thus for λ = 400nm, a 200nm distance will result in destructive interference.

Now what about d0 = 0*λ for constructive interference? Well if the distance is 0, the thickness is 0, meaning there is no film, thus there is just one reflection, no refraction and no second reflection to interfere with the first. Since there is only reflection for all wavelengths at d = 0, the resulting color will be a mix of all the wavelengths available to reflect.

What about when the distance is not exactly constructive or destructive? Like a distance of 700nm for 400nm light? Being exactly between a constructive and destructive distance (600nm and 800nm), the light is neither amplified nor dimmed. 650nm, closer to the destructive distance, dims the light somewhat, and 750, closer to the constructive distance amplifies it somewhat, creating a gradient of intensity.

Index of refraction effect on wavelength

I avoided calling 400nm light violet for a reason. This is the wavelength of the light inside of the second layer, not air. Remember that the index of refraction changes the wavelength. Higher refractive indicies shorten the wavelength. Luckily it is easy to calculate what the wavelength will be in air by multiplying the wavelength by the second material's refractive index.

λair = n*λn

Where n is the index of refraction for a certain material, and λn is the wavelength in that material. Here we are simplifying λair = nλn/nair by rounding air's refractive index of 1.0003 to 1.

Where does λair = nλn/nair come from?

This equation comes from a few other simple equations. Frequency is not affected by a materials refractive index, and is calculated by dividing the wave's velocity (speed) by its wavelength: f = v/λ, where f = frequency and v = velocity. Velocity, the speed of light, is calculated by dividing the speed of light in a vacuum (c) by the refractive index of the material the light is traveling in (n): v = c/n

Now lets plug in c/n for v in f = v/λ, so that we get f = (c/n)/λ, which equals f = c/nλ

Since the frequency (f) will remain constant for one wave, we can say that f1 = f2, and plugging c/nλ for f, we get: c/n1λ1 = c/n2λ2. As a constant, c (2.998*108m/s) can be canceled out from both sides, giving 1/n1λ1 = 1/n2λ2, which simplifies to n1λ1 = n2λ2. Solving for λ2 we get λ2 = n1λ1/n2

So suppose the film was water, with a 1.33 index of refraction. The wavelenth inside of the water was 400nm, so now we can use λair = n*λn to calculate what the wavelength is in air.

λair = 1.33*400nm

λair = 532nm

In order to predict what color reflects most at a thickness, we must convert the wavelength in the film to what it would be in air. Likewise, we must convert a wavelength in air to what it would be in the film, to predict what thickness the color is at.

Note that a material's index of refraction will vary with wavelength (though not by much), which is why I shortened water's refractive index from 1.333 to 1.33.

Multiple wavelengths

With that in mind, lets consider a distance traveled of 1200nm. 1200 is a multiple of both 300 and 400, meaning both of these wavelengths will constructively interfere at this thickness. If the film is water again we can calculate what these wavelengths are once they return to air. λair = 1.33*400nm = 532nm and λair = 1.33*300nm = 399nm. 532nm is green and 399nm is violet; these two colors will mix and be seen as blue (but slightly lighter than a pure blue wavelength). Note 1200nm is also a multiple of 200nm and 600nm, but these wavelengths are outside of the visible spectrum (after converting to air wavelengths).

How about a distance of 1800nm? 300nm fits, 360 fits, and 450nm fits. 1.33*300nm = 399nm 1.33*360nm = 479nm 1.33*450nm = 599nm 399nm is violet, 479nm is teal, and 599 is red orange. This mixture would probably be a muted magenta color.

A distance of 4000nm is a multiple of 500nm, 444nm, 400nm, 364nm, 333nm, and 308nm. In air those wavelengths are: 665nm (red), 591nm (orange), 532nm (green), 484nm (teal), 443nm (indigo), and 410nm (violet). Thats a pretty even mix of colors, so the result would be around white.

You may have noticed that you rarely see pure red in things like oil spills and bubbles, but rather more of a magenta color. This is because the thicknesses that allow red to constructively interfere, also tend to allow blue/violet to constructively interefere, thus the red and blue/violet mix to create magenta!

Phase Shifting

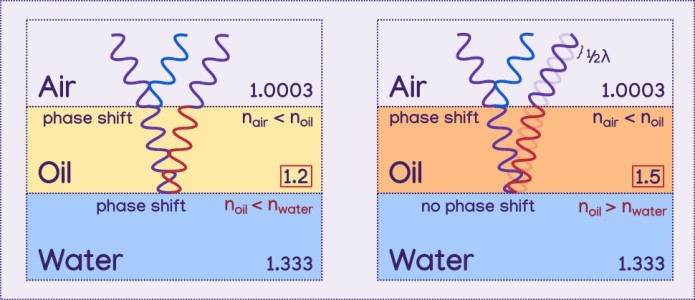

In the previous examples, the second material had a refractive index less than that of the third, but what happens when the second material has a refractive index greater than the third, like it does for a bubble?

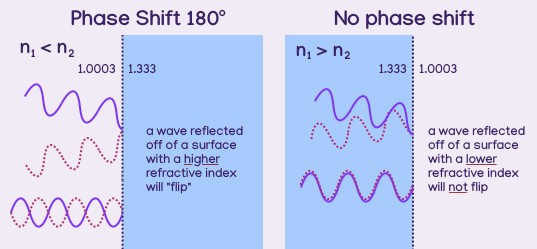

To complicate matters, a wave goes through a 1/2 wavlength phase shift when it reflects off of a surface with a greater refractive index. When a peak hits the surface, a valley reflects off instead of a peak.

Notice how in the example where the second layer has a smaller refractive index than the third, both the intial reflected wave and the refracted wave experience a phase shift. This did not complicate the calculations because they were both displaced by the same amount, half a wavelenth (remember that the distance between two peaks is one wavelength, so the distance between a peak and valley is half a wavelength).

But when the second layer has a larger refractive index than the third, only the intial reflected wave experiences a phase shift, the refracted wave does not, meaning they are off by 1/2 a wavelength in addition to the distance traveled within the second layer.

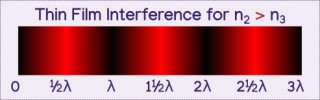

Since we are off by 1/2 a wavelength, our equations are flipped:

d = m*λ + ½λ

Which we can separate into: d0 = ½λ, d1 = λ + ½λ, d2 = 2λ + ½λ, d3 = 3λ + ½λ, etc.

d = m*λ

Which we can separate into: d0 = 0, d1 = λ, d2 = 2λ, d3 = 3λ, etc.

The equations are just switched, but we have to be mindful of the refractive indeicies of the layers in order to determine what distances cause constructive or destructive interference.

Determining distance from thickness

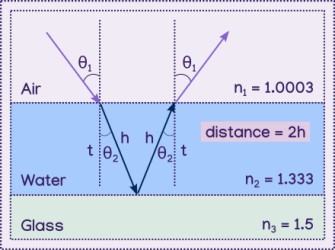

Thickness is easy to determine if we assume that the light hits the surface head on, since it will not refract (bend), thus the distance is just twice the thickness (d = 2t where t is the thickness). So if a film is 400nm thick, the light will travel 800nm within it (400nm going in and 400nm reflected back).

Things get more complicated if the light hits the surface of the thin layer at an angle.

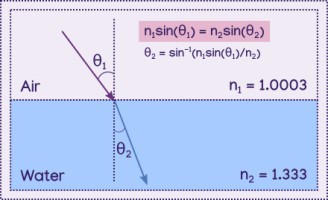

If we know the angle the light hit the surface at (the "angle of incidence") and the refractive indicies of both materials, we can calculate the angle the light makes within the second material, the angle of refraction.

θ2 = sin-1(n1sin(θ1)/n2)

This equation is just Snell's Law, n1sin(θ1) = n2sin(θ2), solved for the angle of refraction.

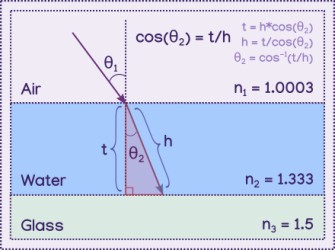

With this angle we can then calculate the distance the refracted path takes within the film.

Usings properties of a right triangle, we can calculate the slope of the triangle (h) from the thickness of the film (t) and the angle of refraction (θ2). The triangle slope (h) is the path of the light passing through the film once. For right triangles, the cosine of an angle equals the length of the side adjacent to the angle deivided by the hypotonuse (the slope) cos(θ) = a/h, in our case the thickness of the film is the adjecent side, making cos(θ2) = t/h. Solving for the hypotonuse, we have to divide the thickness by the cosine of the angle.

h = t/cos(θ2)

Since the light refelects off of the third layer and passes through the second layer twice in total, the distance the light travels will be twice as much as the slope of the triangle.

We know that d = 2h where d = distance and h = a single light path in the film. Knowing that h = t/cos(θ2) we get:

d = 2t/cos(θ2)

Now we can calculate the distance the light travels if we know the angle of incidence and thickness of the film. From the distance we can then calculate the wavelength(s) that constructively interfere the most!

We can now also calculate the thickness of the film if we know the wavelength and angle of incidence:

t = d*cos(θ2)/2

Where we use the wavelength to calculate distance from our constructive and destructive equations: d = m*λ for n2 < n3, and d = m*λ + ½λ for n2 > n3.

Note that this means that the color we see can shift with our viewing position, since the light that reaches our eyes will be from a different angle, changing the distance traveled within the second layer.

Example

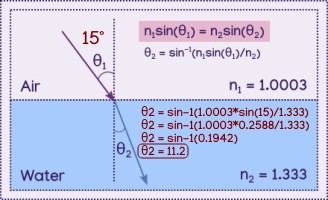

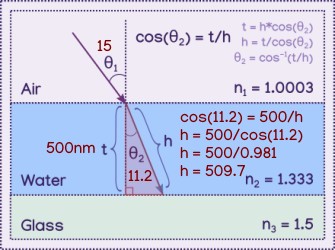

Okay that was a lot of equations, lets use an example. Suppose we have a 500nm thick film of water on glass, and our angle of incidence is 15 degrees. What color will we see at this thickness?

Using Snell's Law (n1sin(θ1) = n2sin(θ2)) we can calculate the angle of refraction (θ2), using the angle of incidence (15), the refractive index of the first material (air at 1.0003), and the refractive index of the second material (water at 1.333). This results in an angle of 11.2.

The thickness of the second layer, water, is 500nm. From our angle of refraction and that thickness we can calculate the distance the refracted light travels within the film of water.

Using the properties of a right triangle when we know the angle and the adjecent side to the angle (the thickness in this case), we can calculate the hypotonuse of the triangle. cos(θ) = adjacent/hypotonuse. Plugging in 11.2 degrees for the angle, 500nm for the adjacent side, and solving for the hypotonuse, we get 509.7nm.

Of course the light reflects off of the third layer, so we must double h, resulting in a total distance within the water film as 1019.4nm. Now lets find the wavelength that constructively interferes the most at this distance.

Glass is the third layer with a refractive index of 1.5, which is higher than that of water at 1.333, which means constructive interference will follow dm = m*λ. For the first non zero distance, d1 = 1*λ, our wavelength would equal the distance 1019.4nm = 1*λ.

Don't forget that this is the wavelength in water, so we must convert this wavelength to that in air in order to determine its color, using λair = n*λn. Plugging in our wavelength and index of refraction (λair = 1.333*1019.4nm) we get 1358.9nm. But this is too large of a wavelength for us to see, we can only see up to 700nm.

So now lets assume the distance is twice the wavelength, d2 = 2λ, giving us 1019.4nm = 2λ, where solving for wavelength we get 509.7nm. Using λair = 1.333*509.7nm we get a wavelength in air of 678.5nm, which is within the visible spectrum!

But there might be more wavelengths that are a multiple of the distance, 1019.4nm, so lets try d3 = 3λ. 1019.4nm = 3λ where the wavelength will be 339.8nm in water. In air this wavelength will be 453.0nm (339.8*1.333), which is also within the visible spectrum.

Trying d4 = 4λ, we get 254.9nm in water, which is 339.7 in air, but this is too small for us to see, being below 400nm. So we are left with our two wavelenths that constructively interfere in a film of water 500nm thick, 678.5nm and 453nm, which are red and blue respectively, mixing to make a magenta color.

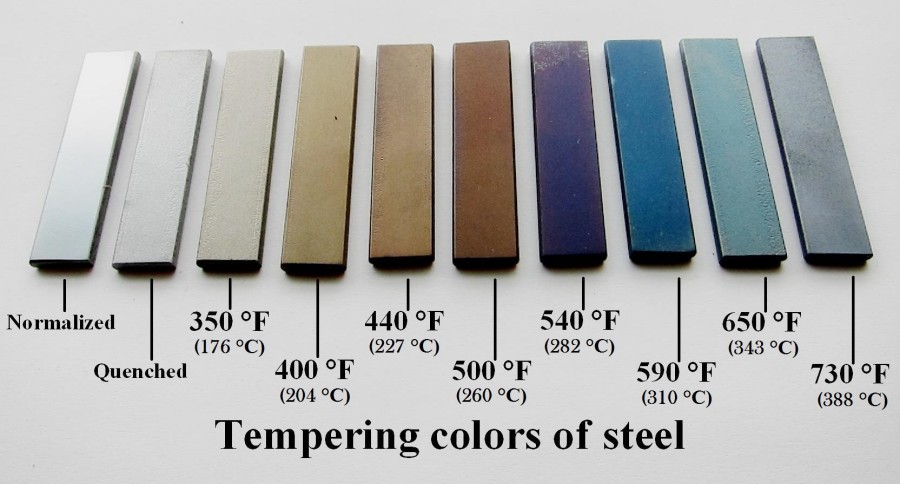

Thin film interference is responsible for heat induced colors in metal. Heating steel will produce a thin film of iron oxide on the surface, where the colors indicate the temperature it was heated to. More heat creates more iron oxide, which thickens the layer.

Soap Bubble Example

With that in mind, lets look at a soap bubble. Soap has a refractive index about the same as water, since it is mostly water.

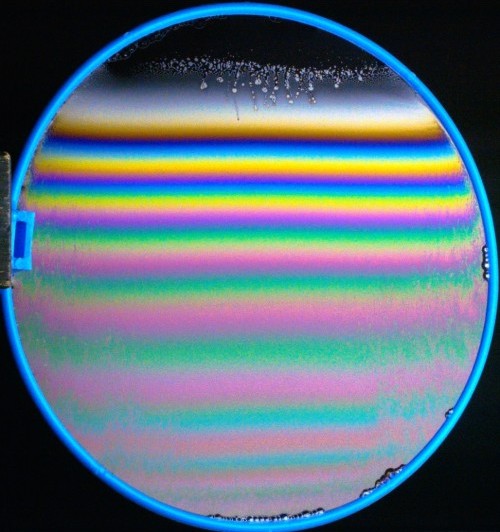

Here is a film of soap suspended by a circular frame, similar to a bubble wand for blowing bubbles. It's held upright rather than parallel to the ground, thus the film is thicker closer to the bottom of the frame due to the pull of gravity. At the top where it is completely transparent is where it is the thinnest. The different colors are different thicknesses.

What color would we expect to see when the film is 225nm thick?

First we are going to assume that the light hits the surface of the bubble head on, so we don't have to do any angle calculations. So the distance the light would travel is simply twice the thickness (in and out): 450nm.

Lets look back at our layers. The second layer, the thin layer, is soap, which being mostly water, has a refractive index of about 1.33. Air is both the first and third layer, having a refractive index of 1.0003. Since our second layer, soap, has a refractive index higher than the third layer, air, (1.33 > 1.0003) our constructive interference equation is:

d = m*λ + ½λ

Lets try d1 = λ + ½λ. We know the distance (d) is 450nm, so we now have to solve for the wavelength (λ). Combining the wavelengths we get d1 = 3λ/2, which solved for wavelength is 2d1/3 = λ. Plugging in 450nm for distance gives us 2*450/3 = λ, so 300nm = λ in soap. Multiplying this wavelength by the refractive index of soap which we assumed to be the same as water (1.33), gives a wavelength in air of 400nm, which is violet!

How about 275nm thick?

The distance would be 550nm, which we will plug into 2d1/3 = λ to give us 2*550/3 = λ, resulting in 366.7nm = λ. In air this wavelength will be 488nm, which is teal!

A 300nm thickness is a 600nm distance. This gives a wavelength in soap of 400nm (2*600/3 = λ), which is 532nm in air, green.

A 375nm thickness is an 750nm distance. This gives a wavelength in soap of 500nm (2*750/3 = λ), which is 666nm in air, red.

At 375nm thick, we are starting to get close to the end of the visible spectrum, for d1 , so lets try d2!

d2 = 2λ + ½λ Simplifying the wavelengths, we get d2 = 5λ/2, which solving for wavelength is 2d2/5 = λ.

So lets try 375nm again but using the d2 equation. Again the distance will be 750nm. 2*750/5 = λ is a wavelength of 300nm in soap, which is 400nm in air. This is violet, but wait! Since both red and violet constructively interfere the most at a 375nm thick soap film, we will see magenta at that thickness.

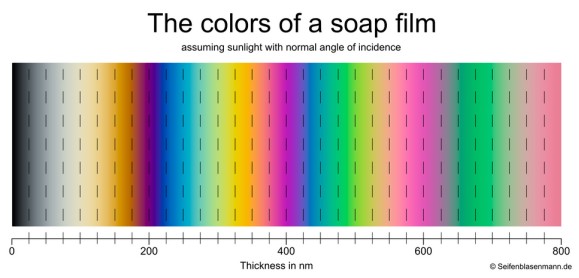

Taking a look at this diagram, we do in fact see magenta at 375nm!

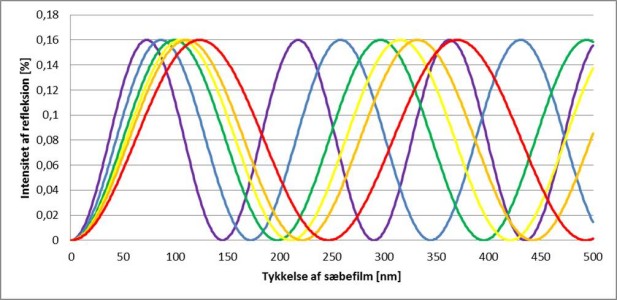

Here is another diagram showing color against thickness of a soap film, but instead of actual colors, it shows the intensity of six rainbow colors at each thickness. A peak for a color is where it is constructively interfering the strongest. Notice how the first peak for each color are tight around 100nm, and how 100nm in the previous diagram is white. The second set of peaks are relatively evenly spaced, creating a nice rainbow. The pattern gets more messy after that.

Newtons Rings

(this section is yet to be written, but in short, newtons rings describe the rainbow rings/bands seen between two layers of glass separated by a thin layer of air)

Suggested Next Page: (none yet)